With fast-fashion contributing over 10% of humanity's Co2 emissions, it's interesting to look back at the last 100 years and map how we got to this point.

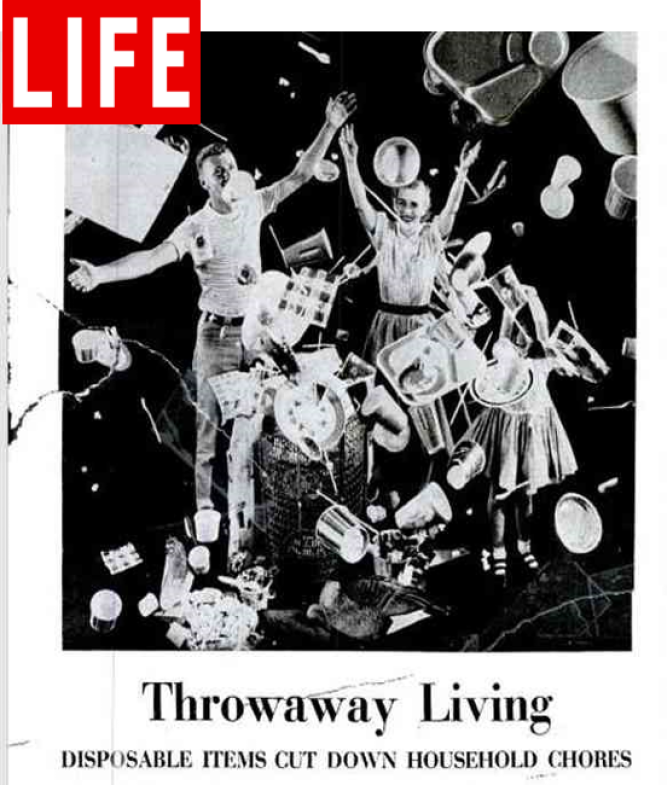

While Life magazine was celebrating the fact that disposable items cut down on household chores in 1955, economist and advertising / marketing consultant Victor Lebow famously promoted the concept of planned obsolescence.

But the concept of planned obsolescence was in no way new in 1955 – in fact we have to go back as far as 1925 to see the initial introduction of a concept that ultimately has driven us to where we find ourselves today. But before we hit on 1925, let’s consider what life was like – from a consumer prospective – prior to 1925.

Life prior to 1925 was one of need rather than want – we sought out products that we needed, rather than products that we wanted. Material possessions were necessities that fulfilled a particular need rather than extras that fulfilled a particular want.

Houses existed to keep us dry, warm and secure and those that lived in the “big house” were a tiny minority.

Transport for the masses was provided by horse & cart, bicycle or even trains for those longer journeys. And that was after the use of one’s legs – most people walked everywhere that they needed to get to.

Clothes were functional – irrespective of age, most people had two sets of cloths, one for daily use and one for attending church on a Sunday. Clothes were handed down without question and repaired wherever possible if damaged. Even the colours were functional – in most cases chosen to continue to look clean when in fact they had become dirty!

And don’t fall into the trap of thinking that the houses, transport, and clothes outlined above were such because of poverty – that is simply not true. How much money a family had may have dictated the size of their house, the pedigree of their horse or the quality of the fabric in their clothes, but only marginally. Just because a family had extra money didn’t mean they spent it on fancier houses, faster horses or loads of clothes.

Prior to the introduction of planned obsolescence as a strategy by industry and indeed by governments in the mid-1920’s, people had a high level of respect for their possessions. Farmers for example were judged by their peers by the way they looked after their equipment rather than by the number of shiny new ploughs they purchased in their lifetime. Pots & pans, crockery & cutlery, beds & blankets – usually initially acquired as wedding gifts – were expected to last forever and were minded as such.

So, back to 1925. On January 15th of that year, a group of leading international businessmen gathered in Geneva for a meeting that would alter the world for decades to come. The group, made up of CEO’s of the top global lightbulb manufacturers (Osram, General Electric, Associated Electrical Industries, and Philips) formed the Phoebus Cartel. The cartel controlled the manufacture and sale of incandescent light bulbs and agreed to purposely reduce the life of their products from 2,500 hours to 1,000 hours, thereby manipulating how fast each product became obsolete and needed to be changed.

In 1927, General Motors opened the first ever dedicated design studio at a major corporation in American history to underpin the GM strategy of “the annual-model-change”. Recognising the risk created by not accurately predict consumers’ changing tastes, GM CEO Alfred P. Sloane believed that GM could actually define consumer’s taste, rather than waiting for the consumer to decide themselves what they actually liked and wanted.

1929 sees the publication of Christine Frederick’s Selling Mrs. Consumer, a book which championed "progressive obsolescence," a plan to stoke consumption by tapping people's love of changing fashions: "The same thrill that women have always had over new clothes, women are now also obtaining over replacement, changes, reconstruction, new colors and forms in all types of merchandise."

In 1932, Bernard London publishes a series of essays that call for ending the Depression through "planned obsolescence," a scheme similar to Frederick's but centrally managed. After a predetermined amount of time, manufactured objects would be "legally 'dead" and recalled. People would then buy new goods, "and the wheels of industry would be kept going."

1954 saw American industrial designer Brooks Stevens popularise the notion of planned obsolescence through advertising, "instilling in the buyer the desire to own something a little newer, a little better, a little sooner than is necessary."

The New York Times coins the term "fast fashion" upon the opening of a flagship Zara store in New York in 1989.

IKEA launches the Chuck Out Your Chintz campaign in 1996, encouraging British consumers to dispose of their stodgy old furniture and embrace the "freedom" of regularly replacing living room furniture.

In 2001, Apple introduces the iPod, which has an unreplaceable battery that lasts only about 18 months.

Fast forward to today - we now have an ingrained culture of progressive obsolescence - a system that sees manufacturers decide for us what we want (not what we need), where having the latest trending item is the norm and where we are made feel second-best unless we embrace the latest trends.

If nothing else, its sure interesting to see how we got here!

Feargal, LilyMais.